Boxworld and AI Pipelining

Table of Contents

- Prior Work, Inspiration, and Goals

- The Boxworld Game

- Project Structure

- How To Train Your Agent (with Reinforcement Learning)

- How to train your Claude

I worked with Claude Code to construct a Reinforcement Learning environment to train an agent to play a simplified grid-based adventure game and then visualize it in 3D. Here's what it taught me about RL (Reinforcement Learning) and pipelining AI code development by iterating on long-term AI tasking.

Prior Work, Inspiration, and Goals

The best way I learn is by encountering a problem and thinking through it for some time until I come up with a solution. I implement multiple approaches, see their respective strengths, and learn what their trade-offs are. The second best way is for me to hear another person walk through their own similar process.

Peter Whidden’s work training an AI to play Pokemon does just that. It is both technically fascinating and extremely entertaining. He outlines many of the challenges he faced and talks through solutions he tried and summarizes what worked. His code is available online.

Andy Coenen’s Isometric NYC is similar. He made a Google Maps-like web project where all the map tiles are stylized isometric images of New York City, where the whole process eventually didn't require human intervention. He documents his outsourcing and refining more and more of the process using AI in an article.

Both of these creative works left me more capable and happier after consuming them. I want to do that for others as well. As a software engineer and technical artist/game developer, the reasons that I made this project were to learn more about Reinforcement Learning, find healthy ways to work alongside Claude Code (changing my prompting and cadence to establish better boundaries on my time), and demonstrate my technical, creative skills to attract a co-founder or potential employer (I'm looking for work).

This project, Boxworld, both trains an agent in a grid-based environment and visualizes it for the web. While I didn't end up using it, Boxworld drew heavy inspiration from Minigrid in its training methodology. Minigrid is an open source framework for “[performing] RL experiments in a controlled setting while being able to increasingly scale the complexity of the tasks.” I didn't use Minigrid because I expected to use a small subset of the available features and wanted to interact more directly with the environment/level (I'll use these two terms interchangeably) creation and training execution.

The Boxworld Game

Rules of Boxworld:

- The agent lives in a world enclosed by boxes on all four sides.

- They want to get to the goal.

- The agent can take one of six distinct actions at any point: move up, move down, move left, move right, pick up a key on the same space, or toggle the door adjacent to them (if they have picked up a key).

- They can only move from the center of one grid square to the center of an adjacent one.

- They cannot move to grid squares with walls. Moving to grid squares with lava is VERY bad.

Project Structure

Boxworld trains the agent offline in a python-based environment. It uses the gymnasium interface to expose the custom game logic to the RL training algorithm. The RL training (more below) is handled by stable_baselines3. After training, some versions of the agent's weights are exported to a SQLite database.

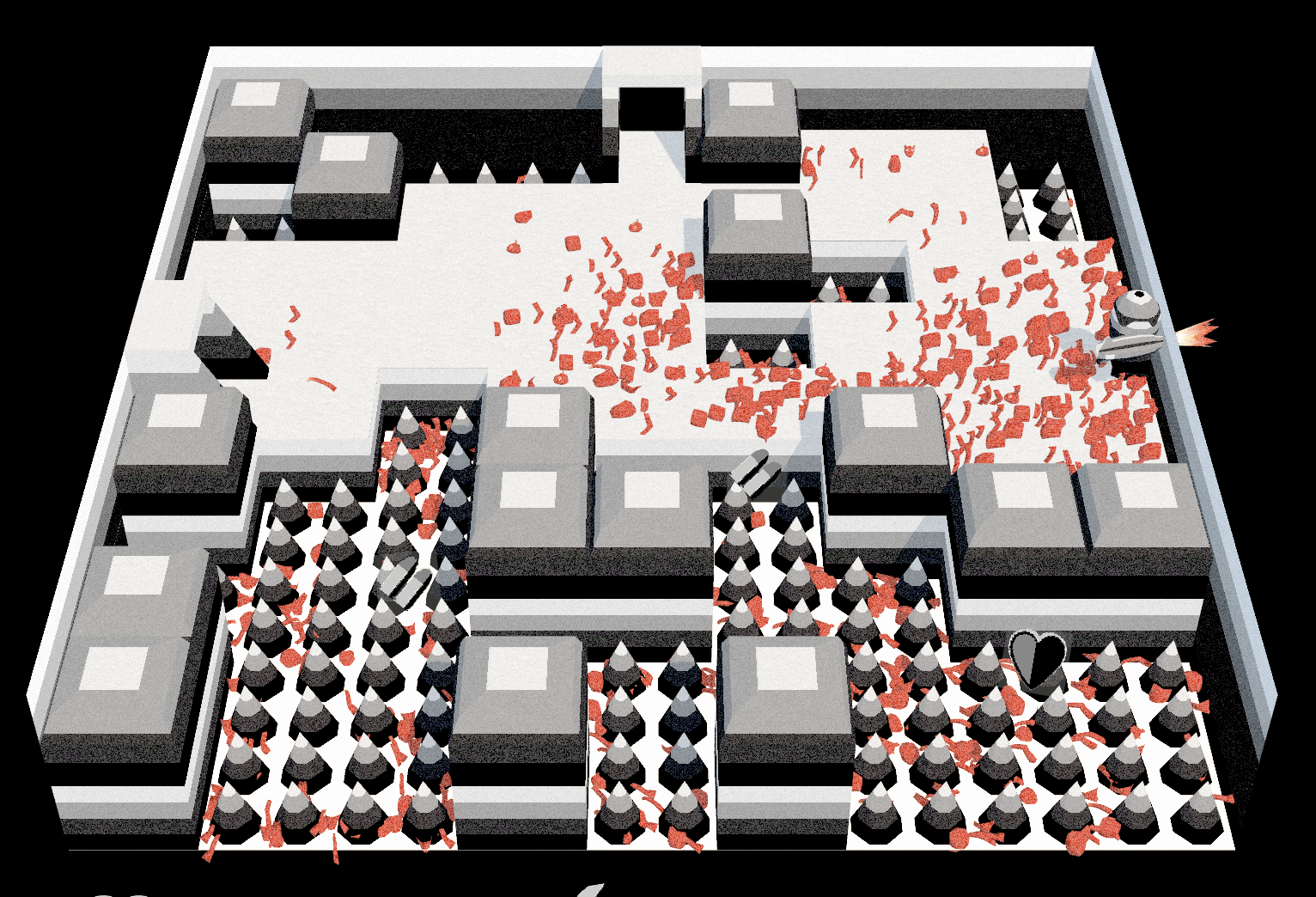

The Boxworld visualization is a React app that uses React Three Fiber (a wrapper around Three.js) to both play back recordings of the agent moving through the environments/levels during the training as well as simulate the agent at different points of its training in custom environments procedurally generated or created by the user.

How To Train Your Agent (with Reinforcement Learning)

RL (Reinforcement Learning) is a machine learning technique that uses a rewards system to train a neural network to take actions in a particular environment. During the research phase of this project, I originally thought DQN (Deep Q-Training Network) would work because I found Deep Q-Learning mentioned in several online discussions of RL. As a game developer, I've implemented many different kinds of games and considered Boxworld to be quite simple, so I didn't spend as much time comparing RL algorithms.

How DQN works

Here's how DQN works at a high level. The agent has some intuition (the Q function) that helps it choose which action to take next in its environment. In the beginning of the training, since the agent doesn't know much about the environment, we set a variable ε (the chance of taking a random action) higher and the agent is mostly wandering around randomly without using its intuition. But as the training progresses, we lower ε because we want the agent to use its intuition to get further and learn more complicated behaviors as the environments we use become more difficult.

After the agent takes an action based on its intuition, we give it a reward to praise or punish certain behaviors. In the case of Boxworld, walking into a wall, walking on lava, moving away from the next goal are all punished (negative reward). Moving closer to the next objective, picking up the key, and opening the door are all praised (positive reward).

And we want the actions the agent takes at the beginning to be informed by whether or not it brings the agent closer to completing its goals. So DQN uses the Bellman equation, which adds to the reward a value that represents the best action available to the agent after it takes the action it just took.

In the beginning, this is basically random noise. But after the agent has been rewarded strongly for finding the goal, the actions that puts the agent within one action of reaching the goal rewards the agent more, and then the actions that put the agent within two actions of reaching the goal rewards more, and so on.

reward = basic_reward + γ * reward_for_best_action_from_new_state

DQN uses a neural network to represent the agent's intuition. The intuition is updated using Gradient Descent. The loss function for gradient descent, the way we measure how well the neural network is performing compared with some better informed prediction, is the difference of the reward we just calculated (better informed prediction) and the reward the agent guesses it would get by taking this action (less informed prediction), squared.

A loss of 0 means the agent perfectly guessed it would receive the reward it did and didn't learn anything. We then use the loss to run backpropagation in gradient descent to update the weights in the neural network.

loss = (reward - guessed_reward)²

In order to make sure updates to the agent's intuition don't “crowd out” previous updates it's incorporated into its intuition, there are two nuances to how the updates work:

- When calculating the loss for gradient descent, we don't just calculate it with this one new data point. We keep track of the last N (e.g. 100,000) actions the agent took and what state the environment was in when it took the action and calculate the loss for a sample (e.g. 32 samples) of those actions as well. This reduces the impact that a series of similar states where the agent took similar actions in succession could have (walking down a hallway) on updating the intuition.

- When determining what the best action the agent can take after taking the action it took, we don't use the intuition from the last update; we use an older, periodically updated intuition to dampen the effect of this single update.

Using DQN with Boxworld

Originally, the agent would train on 5 hand-crafted environments 10% of the time and train on procedurally generated levels 90% of the time. I was only running ~500k steps and training only took 1-2 minutes on my laptop, so I tweaked the training hyperparameters manually myself to see if I could develop an intuition for it. However, the best the agent could do was the ability to solve one of the hand-crafted levels with no walls and one with a simple corridor.

Early DQN training the agent to walk through a simple corridor

Claude Code helped find some bugs:

- The algorithm that calculated whether the agent was moving closer or further from its next objective thought that doors were impassible walls. In the situation where the agent had picked up the key and was supposed to be moving towards a door, the rewards were sabotaging them.

- That algorithm also expected the agent to walk through lava to move optimally, even though the reward system highly punished walking in lava.

So when setting up RL training environments, you also have to not only procedurally generate environments that are winnable, but also ensure that your optimal playthrough part of the reward system is also correct (if that's possible to calculate in your environment).

A clear problem with the training was that procedurally generated levels were too easy and neither representative of the hand-crafted environments in the training nor of the environments the player would want to make in the web UI. They were more akin to walls and doors in random locations.

In a game I developed called There Are Cats, I initialized procedurally generated levels using a random depth-first search maze-generation algorithm, then the paths between doors and a couple random points were walkable and everything else became impassible. I considered using this here, but again it didn't seem like it'd be representative of either environment.

There Are Cats example level

I ended up migrating to sampling from a list of different types of rooms, most of which are based on techniques for generating rooms for rogue-like games, such as BPS, which subdivides a large starting room once or twice into smaller rooms then creates doors/hallways between them.

Another consideration was that each item in the environment (door, lava, key, start, goal, etc) was encoded into the inputs for the neural network as its enum value (0, 1, 2, ...), which could incorrectly give the agent the impression that there's a relationship between how large the number is or how close its value is to other numbers numbers that are closer together.

One-hot encoding was suggested as a fix (i.e. instead of using the number 2, using [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] to represent 2 in a set of five possible values), although I didn't end up using it, as switching to PPO (below) proved more successful. Similarly, Claude Code imparted that the base DQN implementation I used from stable_baselines3 was missing many optimizations, but because PPO worked better, I didn't investigate how to improve the implementation further.

As a newer ML practitioner, I ultimately deferred to Claude Code's priorities regarding which direction to move with the training implementation, investigating why it recommended each solution and considering what I wanted in the final project. After making the changes above and tweaking the hyperparameters at Claude Code's suggestion, I still failed to get a model that solved most of the hand-crafted levels.

That was when I asked about alternative RL algorithms and discovered that PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) with a CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) to represent the intuition had been specifically used to solve similar grid-based games like this many times. The change from DQN to PPO was suggested during one of the Claude's many marathon loops (see below) and I don't have an intuitive understanding of how that algorithm works like DQN, so I won't go into its details.

How to train your Claude

Reusable artifacts

I frequently used Claude Code to help me explore ideas or do research. Because the context window of LLMs is finite, I externalized a lot of content I worked through with Claude into markdown files. When I make the boundaries of the content that can be loaded and unloaded clear like this, it makes it easy to remove the content later when I don't need it, to bring the content into new sessions with Claude, and (3) to document the history of design and development of the project [0].

I used a Claude Code skill called /write-up frequently, asking Claude to record what we'd talked about:

/write-up our conversation

But it was often more specific:

/write-up read @'docs/2026-02-05_Boxworld Visualization Spec.md' and come up with a list of tasks where each one is something a coding agent could accomplish within the context window. Within your task plan, make note of these implementation nudges: ...

Claude also conducted much of the open-ended research that this project demanded, using a /research skill to make web searches, read results, and compile the information while still citing sources.

/research If I wanted to pay to rent GPUs to do the training, what are my options? What is the interface? What would be the general pricing to do 1M steps? Would it provide any speedup over what my laptop is capable of?

Iterating on the implementation

I had a Claude code skill called /explain that shaped so many of the conversations I had with Claude that I integrated it into my CLAUDE.md. The biggest improvement from using it was getting the Claude to respond in 1-2 sentences by default. My motivation is the most scarce resource I have when working on projects and unnecessarily verbose or flowery responses from LLMs saps from my reservoir of energy.

Prompting LLMs is still somewhat of an artform, so I hesitantly added “ALWAYS KEEP THIS FILE IN THE CONTEXT WINDOW” to the top and bottom of my CLAUDE.md file because I've read that LLMs both prioritize text at the boundaries of files and don't use content in files if it doesn't seem relevant to the task at hand [1].

My understanding of machine learning is in specific areas, so in the initial design phase, I asked LLMs to help me explore areas I wasn't familiar with. It's very validating, however, when my own cursory research arrives at similar conclusions to the LLM's exploration (without anchoring it in any specific direction).

For example, I had a sense of the kind of project that I wanted to make, but I still asked the LLM to help me brainstorm ideas and compare it with my own:

I'm a strong programmer (but ML beginner) planning a ~1-week project where I train an AI to play a top-down, turn-based roguelike game, then visualize the AI's playthroughs as an interactive timeline (think SNES-style or Crypt of the NecroDancer aesthetic). I'm interested in shader programming and may add post-processing effects or even project 2D gameplay into simple 3D using color/depth data. I want a comprehensive survey of the landscape so I can pick the right game, the right approach, and produce something that allows me to leverage my shader skills and teach me about reinforcement learning.

... Let's talk about using a training game vs real game. My current idea is to create a web environment where we can use something on top of Web Assemply or WebGPU to actually train a model in the browser in front of the user's eyes, then let them change the level to see how the AI would react. Some of what I'd add might be to create a 3D environment that is visually distinct with post-processing shader. Where is the library game at for training a model in the browser? What about turning the minihack code into something that could be run in the browser? We'd probably provide a pre-trained model for people that don't want to do that. How feasible is it? After you do that, push back against my idea and provide other suggestions, using real games or other research games.

Ask for the interface that you want

One of my goals was to demonstrate my technical, creative skills in the Boxworld visualization. While I'd worked with React Three Fiber components before, most of my experience in rendering engines was with the Unity and Godot game engines and direct WebGL. I was used to working with some standard interfaces, but the interfaces were different with Three.js. I discovered that you can ask for the interface you want.

Asking for a particle system from Claude:

Look at 'visualize/src/render.tsx'. Create a particle system compatible with it that can be integrated into the Fiber scene. Let's talk about the API. I am not familiar with the interface... would it be really difficult to make one where the particle quads are falling in a trajectory according to gravity? Would the position need to be derived from the current time only? What's the interface we should expect to work with? For the fragment shader, it should also take an optional image texture and then the body of a fragment shader (copy the GLSL functions from https://ulyssepence.com/static/shader-canvas.js).

Can produce a component used like:

That looks like:

Asking for a new kind of material from Claude:

I'd like to add to create a new kind of material that takes an optional vertex shader body and optional fragment shader body: - vertex shader should expect the user to change the object space `position` vec3 variable and have as inputs in scope worldPosition, mesh uv, color, screen position, vertex ID, normal, t (time), dt (delta since last time) - fragment shader should have basically the same format as the one in particles.tsx. Defaults to three.js material with basic shading if not present

Can produce a component used like:

That creates walls and keys like:

Marathon loops with Test-driven Development

I spent a significant portion of Boxworld's development trying to improve the RL training. Initially, I had this loop:

- Run the training (2-5 minutes)

- Check the results to see if the trained agent meets my expectations

- Work with Claude Code to come up with optimizations or consider new directions

It was slow. I was heavily involved in the process, but when I made changes to the training, it wasn't always clear how long it would take, so I found myself with poor boundaries with my tool and wasn't managing my time well.

I quickly decided that it would make more sense to take myself out of the loop. I asked Claude to perform a long, marathon loop itself, iterating on the training without my intervention. But how would Claude know if it had succeeded in successfully training the agent? At first, I was naively reviewing the data manually, but that wouldn't work for this new approach. I'd used TDD (Test-driven Development), writing tests first that check the functionality of your application before you implement it, on other projects with LLMs.

Another similar practice in software engineering is to fix bugs by first writing a test that fails and only succeeds when the bug is gone. In this case, during its marathon loop, the LLM might run these tests dozens or hundreds of times as it makes changes and runs the tests to see if it's succeeded.

The first test I used was to ensure that the agent was able to reach the end of each of the hand-crafted levels in the training. This test worked wonderfully to shape the LLM's behavior and after an hour or so, it succeeded! However, there was a problem. The training has a variable designed_level_prob which represents how often the hand-crafted levels are used in the training versus procedurally-generated ones.

The LLM discovered that when designed_level_prob was at 100%, the agent was much better at completing the levels. Unfortunately, that meant that the agent was overfitting; it was essentially memorizing the training levels and not learning generalizable behaviors.

To fix this, I learned that putting some training data aside in a hold-out set that isn't used for training but only to validate it reduced the overfitting problem. Unfortunately, the training wasn't as successful with this method until I raised the training steps from 500,000 to 1-2M. Here's the prompt I used with Claude Code to run this loop:

Let's do a marathon loop until the validation tests pass: (1) Optimize code if tests not passing. Avoid sneaky behavior like changing the tests to be simpler, reducing the size of the grid, re-integrating the hold-out set back into the training set, etc. (2) Run training (3) Run e2e tests, caring primarily about (a) the test that ensures the last episode of each level has the player at the goal and (b) the test that checks against the hold-out set

This generalized better. The agent was able to solve the hold-out level successfully. At this point, I added the ability in the web frontend to generate random levels and edit them. The agent could solve very few of them. The problem was that the nice, procedurally generated levels in the frontend looked nothing like the procedurally generated ones in the training set.

So I changed the procedural generation in the training set to match and created a new training validation test that generated 100 levels and expected the agent to be able to pass X% of them. X% started at 100%, but I noticed that as the LLM ran the marathon loop, that number eventually was adjusted down to 40%, with 2 retries. This, too, improved the generalizability of the model considerably.

But why did the LLM add retries? Because the agent actually uses some randomness when it runs. If you only let the agent use its intuition it's developed deterministically, a small state like the one in Boxworld can quickly lead the agent into unwinnable loops of action. To combat that, there's a little randomness in how it choose which action to run.

Regardless, reducing the percent to 40% with 2 retries reduces the effect of this test. When the user runs the agent live in the web frontend, they won't want to procedurally generate levels until they come across one of the ~40% that the agent can win on one out of three attempts.

By now, the training was going through 10M steps and the agent often finished generated levels successfully. Instead of continuing the training, I decided to tweak the training so that after it ran, it would generate several thousand random seeds that produced levels the agent could win at. These would be the only ones that were generated in the web frontend. It was a hard compromise to make, but I decided it would be more enjoyable for users.

Curious about hiring me or working together? Check out my hiring page. You can also hear more from me on YouTube or Twitter.

Footnotes

- [0] Horthy, Dex. “Getting AI to Work in Complex Codebases” 3 Dec. 2025, https://github.com/humanlayer/advanced-context-engineering-for-coding-agents/blob/main/ace-fca.md

- [1] Mistele, Kyle. “Writing a good CLAUDE.md” 25 Nov. 2025, https://www.humanlayer.dev/blog/writing-a-good-claude-md